A few hours north of Cordoba is a place called San Marcos Sierra.

In September, we decided to spend two weeks working on an organic farm in an area of San Marcos Sierra, known as Rio Quilpo. We signed up through WWOOF Argentina ("Willing Workers on Organic Farms"), after trawling through about fifty possible farms, and we'd spoken to Hugo, the owner of the farm, a couple of times on the phone. I was excited at the prospect of doing some actual physical work - picking fruit, gardening, construction, cooking. I couldn't wait to get there.

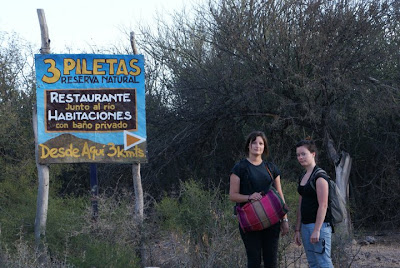

We took a three hour bus to San Marcos Sierra, which broke down. We switched buses and continued on to where we were meant to meet Hugo, who wasn't there. We walked for four hours on the dusty road to get to his farm. I was very inappropriately dressed in jeans and jandals but at least we didn't have our bags, since we'd accidentally (but as it turns out, rather conveniently) left them on the other bus.

Eventually we got there. By this time I had fairly low expectations, but when we saw the place I was still overwhelmingly disappointed. It wasn't even a farm, let alone an organic farm - there were no plants, no garden, no greenery. It was a barren, dusty plot of land by a river. The only people there were Hugo, his 'woman', her son, and another guy called something like 'Hubano' who was helping out. The only animals were five mangy dogs.

Hugo was around his early 40's, with long, greasy gray hair, a beard, and a pot belly. When we turned up he was holding a bird with a broken wing. (I have no idea what he intended to do with it, because I highly doubt that he had any medical knowledge whatsoever that would have helped it). He showed us the room we were going to stay in. Suprisingly, there was an ensuite, though this was the one redeeming feature of the place. It had bunk beds with no sheets and no pillows, some scratchy blankets, and a fire out the back to heat the water for the shower.

Hugo was holding the dying bird the entire time he showed us around. "You can start work tomorrow", he said. "I have not organised anything yet. But we can do tomorrow". We asked him what we would be doing but he didn't seem quite sure. "Cleaning the river, cleaning up, that sort of thing", he said vaguely. "Is all natural here, because all day we clean, clean clean". I looked around. There was crap everywhere - bits of plastic containers, wire springs, broken chairs. He showed us the kitchen next, which was full of dirty dishes, random cooking implements and blatently non-organic food.

Hugo did feed us, I'll give him that. His 'woman' made an amazing pasta sauce, though we were the only three eating it which was slightly uncomfortable. Hugo sat there for a bit, fiddling with something on the table, then looked up and said that it was "time for marijuana". Of course. (I'm pretty sure, at this place, that it was always time for marijuana). I wondered whether he was expecting us all to get stoned together and how I could politely decline, but evidentally he just meant for himself. He lit up a joint on the gas stove and puffed away for about the next half hour, before announcing that he was heading off to a child's birthday party in the town and would see us at 8am the next morning.

That night I went to bed with all my clothes on, so that no part of me had to touch the mattress or the blankets. With hardly any deliberation at all we decided to leave the next day. When we told Hugo (at about midday - there was no way he was getting up at 8am), he seemed fairly okay with it. He just shrugged. "Is it because of Hubano?' his 'woman' asked suspiciously. (She, by the way, was beautiful. I have no idea why she was there on that farm with him). We assured them that it was nothing to do with Hubano (or whatever his name was), or with them; it was just because we wanted to work on an actual organic farm. They seemed pretty satisfied with this. They drove us back into town and wished us well.

Nicola